OXY

Word of the Month

And the last word for this year. Not a word, though, is it. Just a prefix. But a remarkably productive and multifarious one, cropping up in all sorts of strange and important contexts, from oxygen to Deoxyribonucleic Acid to oxymoron.

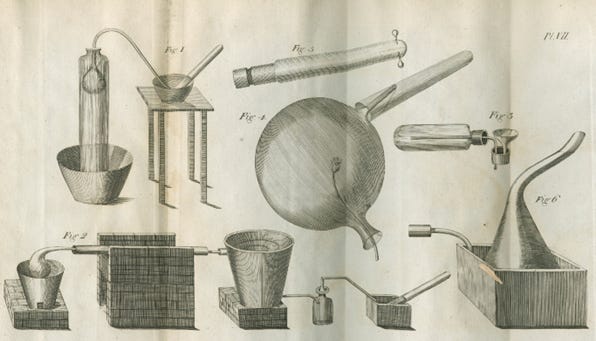

Equipment for the ‘Experiments and Observations on Air’ by Joseph Priestley, discoverer of ‘dephlogisticated air’ (oxygen) in 1774

SHARP, SWIFT, ACUTE

We start with the Greek word oxus (ὀξύς), which means ‘sharp’ – as in a blade. People in Homer, for example, are constantly being struck ‘by the sharp spear’ (oxeï douri) or ‘by the sharp bronze’ (oxeï khalkōi). Then there’s a range of related senses: pains can be sharp in the sense of intense, so too sights, in the sense of bright or dazzling; and indeed the sense of sight itself – or even the senses more broadly.

Well, so far, so familiar: in English too blades, pains and our senses may be ‘sharp’.

And so we get to ‘oxymoron’ (not actually a Greek word but one made up by a Latin author, apparently in the fifth century). The ‘oxy’ part means sharp in the sense of keen or bright, the ‘moron’ part (of course) dull or stupid. So, the word functions by exemplifying the thing it refers to. It’s a word that contradicts itself.

But ancient Greek sounds could also be oxus, in the sense of shrill or piercing. And later, in a more precise technical sense: oxus is high-pitched as opposed to barus, low-pitched. Even more technically, oxus refers to the ‘acute’ accent – which in ancient Greek was indeed a pitch accent. You went up in pitch on a vowel with an acute accent (and stayed down on a grave).

But talking of ‘acute’ leads us to a whole other range of meanings. Latin acutus is one translation of the Greek word, and in both languages the word denotes intensity, especially in relation to diseases. Early on, Greek medicine made a distinction between diseases that were oxus and that were chronios; and via Latin this became the distinction between ‘acute’ and ‘chronic’ that is still with us today.

And finally, yet another sense: swift. Homeric horses as well as spears can be oxus; and an irascible or bad-tempered man can be described as oxu-thumos – ‘sharp-spirited’, meaning ‘quick to anger’.

TASTES AND FLAVOURS

Going back to ‘sharp’. Again just as in English, the Greek word could refer to tastes. And here a knotty problem of translation arises, for those who’ve spent perhaps too much time trying to make sense of the ancient texts. ‘Sour’, ‘sharp’, ‘pungent’, ‘acidic’ …? The last seems anachronistic, suggesting modern chemical conceptions that didn’t exist in the ancient world (though it does get translated as acidus in Latin). Then again, ‘sour’ may not quite capture it. It seems the ancient Greeks (or at least the ones who left writings on the subject) didn’t divide tastes up in quite the way we do. Instead of the four fundamental tastes sweet, sour, salty and bitter, they speak of oxus; tart or astringent (austēros, stuphōn); smooth; and salty. ‘Sweet’ seems to be considered an intensified form of smooth, and ‘bitter’ an intensified form of salty.

That’s all quite complicated and confusing, but the basic problem is that there are several things here – the tart and astringent, which is the flavour of various raw fruits, as well as the oxus – that might correspond to our ‘sour’.

We can be clear, at least, that oxus was the taste of citrus fruits and of certain wines – and indeed of vinegar.

WINE OR VINEGAR – AND SOOTHING OR DISGUSTING?

But even here things are not quite as simple as we might like, because the related noun oxos was used not just for vinegar but for a particular kind of (sour or acidic) wine that was widely drunk in the Roman empire – in Latin posca. Well, it seems that it was somewhere between wine and vinegar, was drunk watered down and flavoured with aromatic herbs, and was pretty much the staple drink of the Roman army. It doesn’t go off (any more than it’s off already); and the acidity presumably masks any taste of dodgy water, and possibly even kills some bacteria. Or, to look at it another way, the herbs disguise the poor quality of the wine. Highly refreshing, anyway, for the raging thirst.

Sour or acidic, then (perhaps a little optimistically) in roughly the same way as the soothing acidity of a not-too-strong craft IPA …?

This, incidentally (oxos, not craft IPA) was the drink given to Jesus on the cross according to the gospels of John (19:29–30) and Matthew (27:34). I had always thought, it seems wrongly, that the sponge filled with vinegar and hoisted up to the dying Jesus was intended as a further humiliation. Well, it’s tricky. That may indeed be the intention of the texts, as they seem to want to suggest the fulfilment of a prophecy in the Psalms (69:21) about being given unpleasant things to eat and drink. Actually (to complicate things more), the accounts in the two gospels are slightly different. John refers to the drink as oxos, says it was flavoured with hyssop, and has Jesus drinking it; Matthew actually calls it wine (oinos) but says it was flavoured with cholē and has Jesus refusing it. Cholē usually means ‘bile’ or ‘gall’, and the sense is a bit puzzling here – possibly a bitter herb, some have suggested myrrh … Or perhaps he’s mentioned ‘gall’ just because it’s in that Psalms text which needs to be fulfilled. Anyway, it certainly sounds less pleasant in Matthew’s account.

Still, taking the two texts together, it seems clear that – insofar as they are reflecting actual historical events – what they are talking about is precisely the herbally-infused wine-vinegar that was drink of choice of the ordinary Roman. Regarded as soothing and cooling, not as disgusting or humiliating.

ACID, OXYGEN …

The ‘acid’ or acidus translation reminds us of one of the main and most curious pathways of the word. Developing a new system of chemistry in the eighteenth century, Antoine Lavoisier coined the word ‘oxygen’ to refer to this newly-discovered element, because he took it to be the essential element of all acids. ‘Oxy-gen’ simply meaning ‘acid-generating’ (his original term was in fact principe oxygène). Similarly, he identified the element hydrogen, and gave it that name because he thought it to be the principle ‘generating water’.

And so the word for ‘sour’ or ‘acid’ survives in our word for oxygen – and in derived chemical terms, where the ‘oxy’ bit on its own refers to the oxygen – long after the theory underlying that word has been superseded.

As a linguistic curiosity, while most European languages have taken ‘oxygène’, or some related form, as their word for the element, both German and most Slavic languages have rather translated the concept. Thus, Russian has kislorod, where the kislo bit derives from the word for acid and the rod means generation; and so similarly Czech kyslík, Croatian/Bosnian kisik, etc. And German retains the wonderful Sauerstoff – the ‘stuff’ that ‘sour’ things are made from – as well as the equivalent, on the same principle, for hydrogen: Wasserstoff.

A curious exception is Polish. Desperate to get away from the outdated theory, a physician named Jan Oczapowski in the nineteenth century coined the word tlen –derived from a word for ‘smouldering’, and thus getting us away from the notion of acid and towards that of combustion.

OXYRRHYNCHUS

And finally, for anyone idly wondering (I’m sure you were) about the origin of the name Oxyrrhynchus in Egypt, source of the famous collection of papyrus fragments which are still being kept, studied and deciphered in Oxford (where they are occasionally also the focus of some bizarre scandals) … it seems that it refers to a particular kind of ‘sharp-snouted’ fish, which must have been a speciality of the area.

HAPPY NEW YEAR

Wishing everyone a happy New Year, and many happy oxymorons (itself an oxymoron?) in the year to come.

Thanks Peter, always inspired by your erudite comments and discussions, here and at online meetings. Happy New Year and best wishes for 2026!

Lovely! Always truly enjoy linguistic excursions of this kind :) Wish you a happy new year too.